Upward. 3

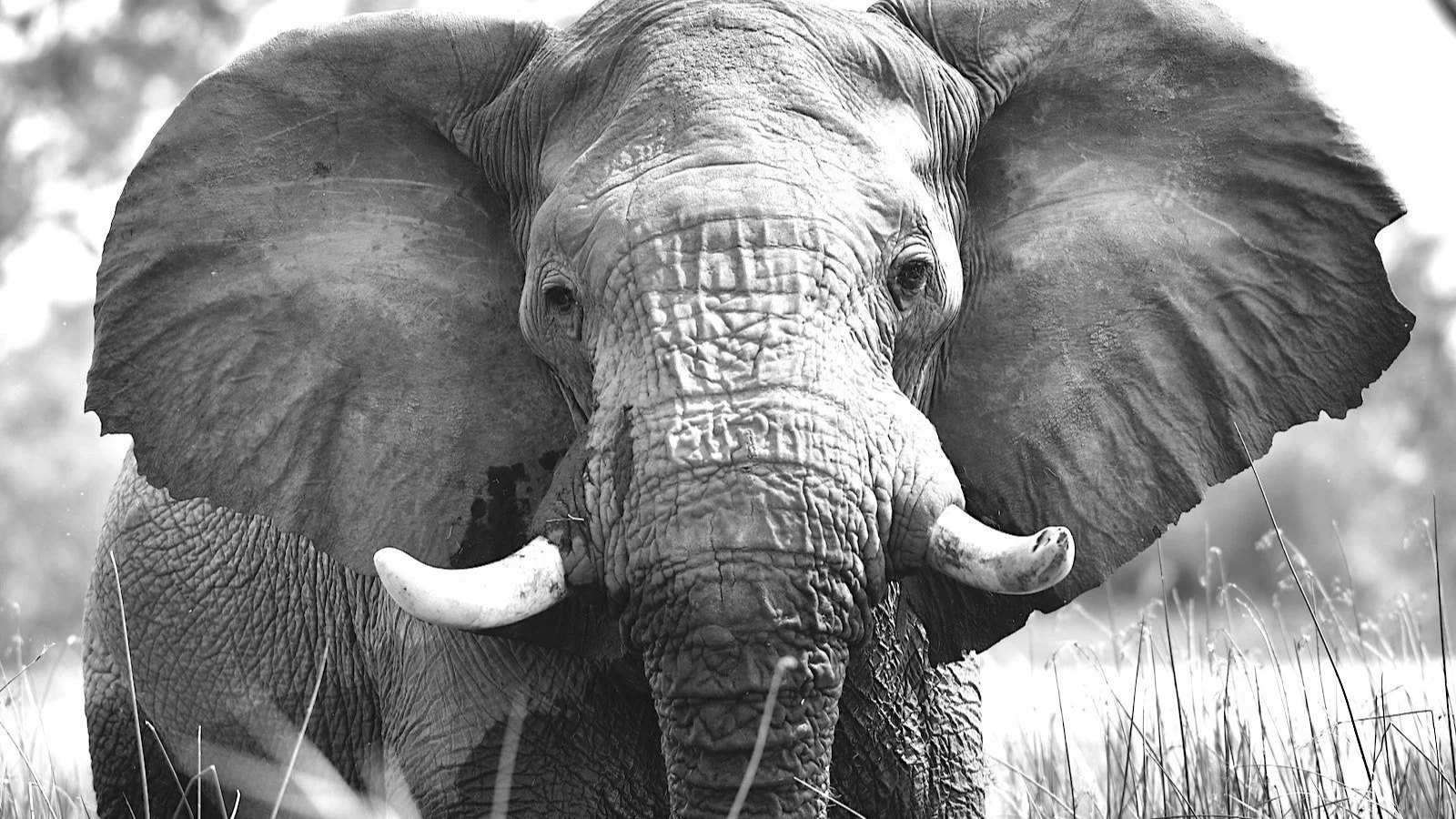

Elephant

The third in a series of posts inspired by our current Book Circle on Falling Upward: A Spirituality for The Two Halves of Life, by Richard Rohr. Previous post here.

Perhaps you’ve heard the story of ants on an elephant, each trying to describe the nature of the beast. “Long and rough like a big snake,” says an ant perched on the trunk. “No, it’s tall and solid like a tree,” says one circling a massive leg. “Are you guys crazy?” says a third. “An elephant is narrow and hairy like a rope,” says one attached precariously to the tail. This anecdote, humorous from our omniscient perspective (compared to ants), says something about the “theology” of an elephant… and about theology in general.

None of us gets the full picture when it comes to God and the shape of reality. But we certainly have parts of it.

In this series of articles, we’ve been exploring the idea of there being two halves of life—two exceedingly different experiences of life with different viewpoints, relationships, and priorities. One half that prepares us to “fall” into the next. If this paradigm describes the spiritual journey accurately, perhaps it offers us a helpful perspective on the biblical narrative as well, with the idea that the inspired text also contains commentary from “ants” about an “elephant.” Commentaries that reflect different stages in the evolution of faith.

One of the precious few courses I remember from seminary three decades ago was one entitled “Continuity and Discontinuity.” My professor probed the question of whether the New Testament was more of a seamless extension of the Old Testament (continuity) or a radical shift from the Old Testament (discontinuity). The course offered perspectives and rationale from theologians on both sides of that divide while leaving the conclusion open for interpretation.

At the time, I came down firmly on the side of continuity. I mean, if God is the author of this thing, how could it be otherwise? God isn’t schizophrenic! Thirty years later, however, I am struck by the discontinuity between the two testaments and the progressive nature of revelation in general. Two halves of the “life” of God’s people, with many movements even within the halves. At least that’s the way it makes sense to me.

I think this is a key point where Christ-followers tend to get confused. It’s easy to view the Bible as written by God, dictated as it were to 35 different “secretaries” for publication in 66 books. A slight but vital shift is to recognize these books as inspired by God but written by humans. This doesn’t make scripture any less trustworthy; instead, it lends great light to the development of biblical perspectives over time.

“God-breathed” is the beautiful NIV translation of Paul’s take on things: “All Scripture is God-breathed and is useful for teaching, rebuking, correcting and training in righteousness” (2 Tim 3:16). Theopneustos is the Greek word, a combination of “God” and “breathed,” a callback to God breathing into Adam the breath of life. Inspired… or perhaps better, “expired”—breathed out from God’s heart into human hearts and then translated through culture, geography, chronology, education, and linguistic nuance into words on a page so that, 2000 years later, we have divine ideas filtered and colored by human souls for our comfort, direction, and illumination. I call that inspiring!

This developmental, discontinuous, ants-on-an-elephant approach to scripture helps me reconcile the parts of the Bible that, from our twenty-first century perspective, feel incongruous with the nature of God. Scenes like God requiring rebellious kids to be stoned or rebellious people groups to be exterminated. It provides a necessary context for Jesus saying, “You’ve heard it said… but I say to you…” (five times in Matt 5). The biblical story is a narrative in motion, enriched by various perspectives and viewpoints.

Theologian Walter Brueggemann encourages us to “start with the awareness that the Bible does not speak with a single voice on any topic. Inspired by God as it is, all sorts of persons have a say in the complexity of Scripture, and we are under mandate to listen, as best we can, to all of its voices.”

The first three gospels are often called the “synoptics”—the story of Jesus seen through “one eye,” as compared to John who tells the story quite differently. The term synoptic, though, I find a misnomer. Each of these three views are quite distinct as well. Take, for example, the Beatitudes…

We’re more familiar with Matthew’s version: Blessed are the poor in spirit. But Luke casts it this way: Blessed are you who are poor. Matthew says, Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness; Luke says, Blessed are you who hunger now. Matthew says, Blessed are those who are persecuted because of righteousness; Luke says, Blessed are you when people hate you.

Can you feel the difference? Matthew spiritualizes the blessings of Christ where Luke humanizes them. One is slanted toward matters of the heart while the other is slanted toward matters of the body. They are not in conflict with one another; they’re complementary. Different truths, different perspectives, different places on the elephant.

growing the soul

When you look back on your spiritual journey, how do you find yourself moving from one perspective to another, evolving from one narrative to another?

serving the world

As your spiritual story is being written, how does that affect your ability to respect the stories of others—other “ants” on the “elephant”?

takeaway

Let your story grow.